In a historic meeting in February 2017 Dennis Peron uttered the words "Mike, Compassion doesn't mean convenience - nobody ever left Market Street without a joint."

And those words ring true today. Way back when Dennis and the crowd didn’t let people leave without something in their hands but what he was stating to me was to stop complaining about those who will not follow the leader as he did and I chose to follow him – and instead promote love. He finished this statement as we sat down to write the Peron Resolution requesting an end to Prop 64 prohibition on gifting with “but why should anyone listen to me? I’m just an old gay hippie.”

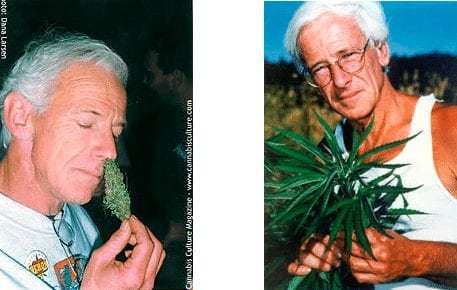

He was more like a legend that spearheaded the Prop 215 team in 1996 that forever changed the world by making Cannabis medicine again in California. In this awesome interview published after he left our world and crossed over to the other side where the plants keep on growing, Dennis tells his story:

“As a young man, Dennis Peron had a ringside seat to a few of the most traumatic events of late-20th century America. Having witnessed war, persecution, brutality, and disease firsthand, he became a staunch opponent to the war on marijuana, battling the forces of prohibition for decades. Any person who has ever smoked a legal joint owes a debt to Dennis Peron, whose 1996 initiative, Proposition 215, legalized medical pot in the state of California. With his death on January 27th, we lost a steadfast voice for the oppressed, but the freedom that he fought for lives on in the form of a steadily declining arrest rate, increasing awareness of the medical benefits of marijuana, and an exploding $7 billion legal cannabis industry.

In 1967 Dennis Peron joined the Air Force to escape conservative Long Island, New York, and was sent to Vietnam. Upon his discharge, he loaded his duffle bag with two pounds of weed and made his way to San Francisco, where he opened a café in the Castro district and began openly selling marijuana. Busted time and again, Peron launched the first of several voter-driven legalization initiatives. His boyfriend, a young openly-gay politician named Harvey Milk, helped him collect signatures. On November 27, 1978, while Peron was sitting in jail on a pot charge, Milk and San Francisco mayor George Moscone were assassinated by a disgruntled former city supervisor named Dan White. White made a case at trial that he had been driven temporarily insane from eating junk food. In a perversion of justice that caused the city’s gay community to riot, White was convicted of manslaughter rather than murder and sentenced to seven years in prison, of which he served only five. (Two years after his release, White committed suicide.)

As the AIDS epidemic began to reach critical mass in San Francisco, Peron provided marijuana to patients who found that it was the only thing that helped them eat during their treatments. One such sufferer was Peron’s own boyfriend, Jonathan West, who was brutally beaten during yet another police raid at Peron’s home. At trial, West testified that the weed found in the raid was his and not Dennis’, then died two weeks later. In jail, Peron had a vision of a safe space where sick people could come and buy marijuana. This idea would alter the trajectory of his life.

After establishing the Cannabis Buyers Club at several underground locations, in 1995, Dennis Peron opened a very public, very illegal medical marijuana dispensary that worked out of a storefront on Market Street in San Francisco. Chalkboards announced the day’s varieties and prices, non-alcoholic refreshments were served, and a wheel-chair friendly lounge area encouraged group medication. Guess what? Peron was busted again.

Proposition 215, the voter-driven initiative to legalize medical marijuana in California that he sponsored in 1996, changed the game. Pot smokers were no longer on the run, they had a political voice—one that reached the ears of billionaire George Soros who committed money to the cause but who demanded control of the campaign in return. Considered too incendiary of a spokesperson to be the face of legal pot in California, Peron was sidelined. Proposition 215 was passed, medical marijuana was legalized in the state, and Peron was soon arrested again for distributing marijuana to the sick.

This interview, part of The Outlaw Marijuana Oral History Project, was conducted in September 2015 at the Castro Castle, a bed and breakfast Dennis ran with his husband and fellow activist John Entwistle in San Francisco. Dennis was in a reflective mood that day, musing upon the Vietnam war, the gay movement, and offering candid critiques of both the marijuana movement and the heavily regulated legal pot industry.

Chris: Do you mind if I ask you about your military service in Vietnam? Did you try to get out of it?

Dennis: I tried. I definitely didn’t want to go to Vietnam. When I went down to Whitehall Street [the induction center in New York] they were like, “You tell us you’re gay? We need some queens in the service.” He told me right away. “Flat feet? We got flat feet. Don’t try that.” Everything I tried wasn’t gonna work. In a way, when I got drafted, I thought, I’ll get out of this hometown and become a person. I couldn’t be gay in New York. I joined the Air Force. Before I know it, oh shit, 1967, I’m going to Vietnam.

Before I leave, someone tells me San Francisco’s a very cool place. “Oh, I’m leaving from there. I’ll go early and hang out.” It’s the Summer of Love. All of a sudden I’m caught up in this thing. It’s all crazy. I ate acid with a bunch of people. I had a 20-day leave. Twenty days come and go, and I’m a hippie. I like this tribe. They’re the only ones who have really accepted me.

Chris: So you got to see 20 days of the Summer of Love and then you got shipped off to combat?

Dennis: Yeah. I was stationed in Saigon. Then the Tet Offensive happened. The city of Saigon was under siege. They had half a million troops in Saigon fighting house-to-house. It made me a little panicked. They said, “Here, Peron, take this gun.” I said, “I can’t take this gun.” “Why not?” “I close my eyes when I shoot.” “Take the gun.” I said, “Who do you want me to shoot?” They gave me an order: “Shoot the Vietnamese.” There were Vietnamese everywhere, and I kind of liked the Vietnamese. “If you give me this gun, I’m going to shoot the wrong person. Don’t give me a gun, I’m afraid of guns.” They said, “Okay, smart guy,” and they assigned me to the morgue for 30 days.

I’m 19, I’ve never seen a dead person, and all of a sudden there are thousands and thousands of dead people. My job is to put them in body bags, put them in caskets, and ship them back to the United States. Sixteen hours a day putting young people in body bags. That month, 20,000 people died. I totally turned against the war, and totally came out of my closet for the first time. Coming out of the closet never was an easy thing to do. There are a couple of stages. First, you come out to yourself, and you think, oh God, I’m gay. I knew I was, but I didn’t know how gay I was. Then you come out to your friends, and then you come out to the public. And I knew I couldn’t come out to the public because I was still in the service.

Chris: Did you get high during the Tet Offensive?

Dennis: Oh yeah. I’m glad I had about four or five ounces that I had just bought before Saigon closed. We couldn’t go to Saigon during the Tet Offensive, we were stuck on base, and I had the only pot. Eventually, we ran out. By the time we were allowed back outside the gate, the man who was selling pot, now he was selling heroin—heroin-laced pot. I knew things were changing.

Chris: You were in for four years?

Dennis: Yeah. I wasn’t back three months before I got my first bust for smoking a joint in Golden Gate Park. I tried to outrun them. I’m 22, just back from Vietnam. I gave them the worst chase of their life. I nearly got away, but I was on acid. They took me down to jail. This guy next to me was joking around. I started laughing. And a guy in charge said, “Shut up, quit laughing.” But the guy next to me said something funny again. The guy in charge said, “I told you to stop laughing!” I said, “Okay, I won’t laugh.” Then someone said something and I couldn’t help it, I cracked up. The guy in charge pointed to me and said, “Okay, you.” He put me in the hole. It was traumatic. Here I was on acid in the hole—a dark room with pee and shit. In the darkness, I was just hallucinating everywhere. I thought I had been captured by the enemy, that the Vietcong had got me. What I always feared the most was becoming a POW. And now I thought I was a POW. I woke up and wasn’t—but I was.

I was very angry. I’d worked for the man for four years. I’d done their bidding. They still hadn’t thanked me. So that resentment came from how they treated me. It started a long string of busts, and one of the times I was busted, I was shot.

I thought it was a rip-off. There was this big guy with a gun, dressed in a fatigue jacket, looking like a thug. You can’t tell the difference between thugs and cops. They’re kind of interchangeable. So this thug comes up the stairs. I do the best thing I can do, I grab a bottle and throw it at him. Then he shoots me. The bullet picks me up and throws me back into the room. The guy comes into the room. He has more guns. I say, “What do you want, money? Here, take the money.” He’s got the gun just like that. He’s actually gonna shoot me, I’m gonna be dead. Then another cop comes in, a narc. I still thought it was a robbery. He goes, “What’s going on?” And the guy put his gun away. He was going to plant a gun on me, but the other cop walked in and surprised him.

It was a long trial. Four months. They were robbing some of the pot I had from the locker room. Beautiful Cambodian. There was less and less and less of it. Eventually, they had to admit it. “We have a mouse in the hall of justice.”

Chris: How many pounds were missing?

Dennis: About a pound and a half. Big rats there.

Chris: Big rats that sit around drinking coffee.

Dennis: And smoke Cambodian. [During the trial] I had an antagonistic relationship with the guy that shot me, Paul Makaveckas. I was kidding him. “You know Paul, I love your shoes!” And I gave him two snaps. It drove him crazy. It was too much. “You faggot, you motherfucking faggot. I should have killed you. There’d be one less faggot in San Francisco.” He said that to me. But he didn’t know the judge was standing right behind him. The judge heard it. So he had to say it on the stand. “You know, I hated this faggot, yeah.” You saw his neck throbbing. He was angry. He was out of his mind. “Let’s talk about the shooting. Show us how you shot Dennis Peron.” He was at a witness chair, pulled a gun out from his waistband, cocked it, and pointed it at me. The judge said, “No more guns in the courtroom,” and he threw out the guy’s testimony against me.

The pot’s being robbed, the testimony is being tainted. I’m thinking, maybe I’m getting away with it. I had 200 pounds of pot and a quarter-million dollars in my twenties. Plus acid, peyote—I had ‘em all. Eventually, I had to make a deal. Six months in jail for 200 pounds of pot. Not too bad. I made a complaint against Makaveckas and then he got reassigned to the taxi bureau. He’s in the news right now.

Chris: Right now?

Dennis: Right now. He took bribes from taxi drivers. Federal court, FBI. He has just been sentenced to two years in jail. I told him I’d be a pen pal for him.

Chris: Did you contact him?

Dennis: Yeah, I did. I try not to hold hate in me. I emailed him. “Do you want to be my pen pal?” I felt for him. Two years. I think it’s a metaphor for the war on drugs—how it bites them and later on, we bite back.

Chris: Well, you won the war on drugs.

Dennis: I did.

Chris: A big battle.

Dennis: It was a big battle. I was willing to give my life for it. And Harvey Milk did give his life for it. “Peron, Milk, and Moscone make San Francisco a cesspool of sex and drugs,” they were saying. I was on Dan White’s hit list, but at the time I was already in jail for the marijuana thing. He couldn’t get to me, but I was on that list.

[The phone rings. Dennis has a short conversation and hangs up.]

Dennis: Drug people. Go ahead.

Chris: When I interviewed Dana Beal, he said he tried to make you a Yippie.

Dennis: He did make me a Yippie, and he taught me everything I would ever need to know about dealing. Because I’m one of those people—I pay $10 an ounce, I sell it for $11. Dana, more than anybody, gave me a concept of the power of money. Dana said, “Don’t sell it for $10, sell it for $15 and use that money to achieve the goal to legalize marijuana.” It made sense to me. I started doing it. Before him, I didn’t want any money. I took a vow of poverty on an acid trip right here in San Francisco when I was 19, off to Vietnam. I said, “I don’t want any money, all I value in life is my friends and my freedom.” I wanted to live simply. I wanted just a boyfriend, an apartment. Dana taught me to think I could change the world. I saw myself as a little ant here in San Francisco. Dana saw me as a world-class player. By doing that he opened my horizons to actually change the world.

Chris: I was talking to someone recently who told me that, around the time you were working on Proposition 215, they witnessed a big argument you had with [hemp activist and author of The Emperor Wears No Clothes] Jack Herer about your competing legalization initiatives.

Dennis: I tried to talk him out of his initiative. It was too long, too complicated, and he insisted on the hemp thing. I told him it was the wrong way to go. He convinced me that I should cut out potheads, that I’ve got to go for another audience. What I’m gonna do is bring in doctors and nurses. It was much more effective. We used George Soros’ money in the end, but I raised a lot of money by myself. A lot of it came from sympathy for the AIDS community. We had a disease running wild. You’re hungry, you haven’t eaten anything in weeks. All these depressed people. There’s a disease that there’s no cure for and you’re gonna die. Does that show up on an X-ray? The pain of knowing you’re gonna die? I wanted to help those people.

[My adversaries] said I was pulling a con job on the people, but they were the ones who were pulling the con job saying that marijuana was dangerous but never explaining why. It was just a lie that kept repeating itself until eventually, it was believable.

Before Prop 215, we passed three bills that were sympathetic to the marijuana community. So that was part of it. I had primed the pump. But these people, look for your weakest link, and my weakest link was political. Politics. And they went through all my enemies to divide it. We got on the ballot, and the people [I was working with] felt I was too radical to write the ballot arguments [for Proposition 215]. I wrote one that was really powerful and articulate. They wrote one that was really measly, mealy. It was just the [ability to use a medical marijuana defense] in court. The right to use marijuana is not a defense, it’s a right.

Chris: Do you see the marijuana movement as being too willing to cooperate?

Dennis: They act like they have Stockholm syndrome. They’re shell-shocked. They’ve been under fire for so long. They’re willing to give up their rights to the man because they’re so afraid. “Oh, he has a point, we better give him something.” The thing is, freedom is not a hyphenated word. There’s no partial freedom, there’s no somewhat freedom. You’re either free or not free. I think a lot of people don’t understand that in the movement.

Chris: Do you see similarities between those who tried to legalize marijuana and the gay rights movement?

Dennis: Yeah, I do. The perspective is that the government is trying to regulate everything. Trying to regulate sex. The most basic thing. Gay people have special anger for the establishment doing that and a special understanding that if you give these guys an inch, they’ll take a mile—regulate your sex life. You can’t regulate blow jobs, but there are people that think, “Well, two blow jobs a day, that’s all you need.” [laughs] Sex is disgusting as far as most people are concerned. “Two blow jobs a day is too much! Why not just one?” They’ll try and minimize everything. I think a lot of the movers in the marijuana movement have been gay, but they have Stockholm syndrome. They just make themselves sound like the moderate and make me sound wild and crazy. In fact, I’m the only one who’s making any sense. I’ve had to endure that my whole life. Being a gay person, there’s a lot of ridicule and a lot of resistance. So that prepared me for the battle. I wasn’t giving up an inch.

Chris: You were gay and a Vietnam veteran. You must have been prepared for anything that they were going to throw at you.

Dennis: They threw it all at me. I think I defended myself nobly. I never sacrificed the movement or my own human rights. For that reason, I still hold my head high. And thank God for my enemies. I always said, [former California Attorney General and Prop 215 opponent] Dan Lungren, thank God they sent me him. I couldn’t have done it without him. He’s such a fool.

Chris: He brought the best out of you?

Dennis: He did. And he showed the worst of what they were about. Very few people win, and then the gay guy wins. They hate that. It affronts their masculinity. It affronts everything that they stand for. So they have a special hate for me. They will do anything to get me. They’ll troll around trailer camps saying, “Give me something on Peron.” They couldn’t get anything so they had to make up shit—and half the shit they made up wasn’t even true.

Being gay is a flaw when entering politics, but it’s getting less so. Doing Prop 215 I said, “Look, who is going to be the front? Not me.” They looked at me, “What do you mean?” I go, “I’m a gay guy who’s been in and out of jail my whole life. I’m not the guy. I can’t be the guy. Get somebody else. Someone cleaner, some nurse or something.” So I recruited [registered nurse] Anna Boyce [to be the frontperson of Prop 215]. I found her in Sacramento. She didn’t smoke which was a problem. Because if you don’t smoke, you don’t understand what we’re fighting for. You can’t explain to someone who doesn’t smoke, the consciousness they’re gonna get, how it’s gonna change them.

Chris: Do you think the legal marijuana market is too straight?

Dennis: Yeah, I do.

Chris: It’s too legal?

Dennis: It’s too legal. And too maternal. They legalize it to death. There’s a simpler way, not regulating. You trust people to find their own way. I think that’s what it comes down to. You can’t regulate a plant. They’ll drag it out for another 10 years, then they’ll throw their hands up. “We can’t regulate it, we can’t do anything.” Eventually, we’ll win.

Chris: A lot of veterans today see marijuana as the only effective way to alleviate PTSD. As a combat veteran, do you see a connection?

Dennis: To this day, I go to sleep and I think about how the war affected me, how many stories are not written, all those young kids I put in body bags. There’s a smell, the smell of death. The smell never gets away from you. I’ve learned to live with it. I’m haunted by it. I’m haunted by everything. I’m haunted by the Vietnam war, I’m haunted by the war on drugs, I’m haunted by starving people. Marijuana does help me with all this haunting, but I’ve mostly learned to live with the contradictions in life, live with the sadness and the deprivation and desires. You can’t solve all the problems. At least we have marijuana to help us. While I was growing up I thought, Dennis, you’re gay, Liberace is your role model, you’re Italian, you’ve got a fucked up family, you’re white trash, but at least you’ve got marijuana. It’s your friend. It’s your advisor. It’s your buddy who will never leave you. It saved my life. Damn sure. “I’m gay, oh God, everyone hates me!” At least I’ve got marijuana. It doesn’t hate me, it loves me.

It’s beyond intense to read this and even more intense to publish it once again. Thank you to the folks at Paradise Burning for their reprint of the interview as well as The Outlaw Marijuana Oral History Project for all of your hard work in allowing people to read about and know who Dennis Peron was. Daily it’s amazing how many will end up in a chat and the name is dropped with no recognition – taking the time out of a busy day to teach someone about Dennis means you’ve taken your time to spread love as that’s what he was all about.

The man loved the world and Prop. 64 hurt him – the prohibition of the ability to give away cannabis and oils had to be the most brutal blow that he faced throughout 20 years of celebrating. I’ll never forget being invited to that 20-year celebration literally held right before Prop 64 passed in California allowing for adult consumption and forever putting the work of the hippies in the rearview mirror. The love, the compassion, the subculture that brought cannabis back into the spotlight was seriously stepped on by the need for greed.

-Mike Robinson, Cannabis Patient and Founder, Global Cannabinoid Research Center. But, most of all, Genevieve’s Daddy

Sign up to receive informative and exciting email updates from Mike's Medicines!

You can sign up for our mail list here:

Didn't find what you are looking for?

Find exactly what you want to when you want it.

Browse through our archives by date, category or by entering a topic in the provided search field.

Archives

Categories

More to come as we have time to add them – there’s 100’s of additional publications!

We’ve made it easy for you to read Mike’s Medicine Blog or visit any of the Menu items right from here. It is that simple! Explore Mikes Medicines by clicking on the button below:

Read about how Cannabis Compassion and love created Mike’s beautiful family, the Cannabis Love Story inspires millions daily:

Genevieve’s Dream is all about her love for the Carousel coupled with her Cannabinoid Medicine journey – read more and make contact if you’re interested in collaborating with Mike!

The Global Cannabinoid Research Center is a trusted source for education, R&D, and more – make contact with us to collaborate.